Previous Exhibition:

Albert Clarke

Albert Clarke |

Giles Gilson

Giles Gilson

|

Nikolai Ossipov

Nikolai Ossipov

|

This exhibition is being presented at the Center and online with Artsy,

alongside an international community of museums, galleries and auction houses.

View Exhibition on Artsy

Following is a short history of the American Studio Craft Movement, followed by a personal perspective, to provide context for the exhibition.

The American Studio Craft Movement can best be understood by looking at what influenced and led to it, as there’s a philosophical basis to it all.

For the most part, the artists who were active in creating the American Studio Craft Movement didn’t necessarily view themselves as an extension of the Arts & Crafts Movement. However, they were aligned with it in many ways and – in the larger scheme of things – reinventing and continuing it.

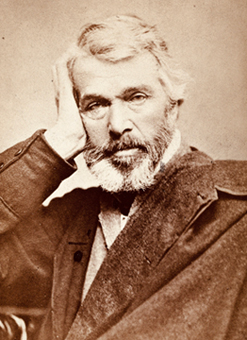

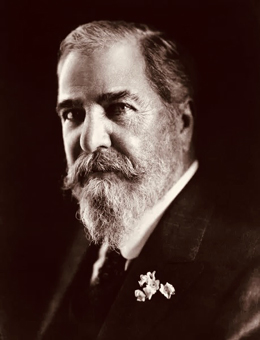

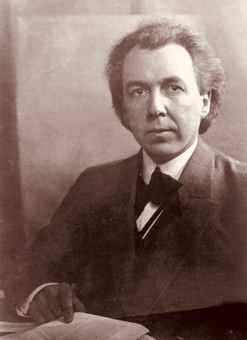

Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle |

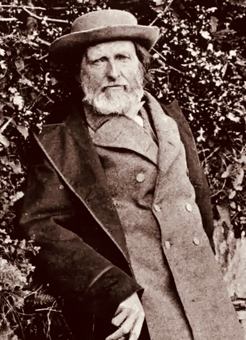

John Ruskin

John Ruskin |

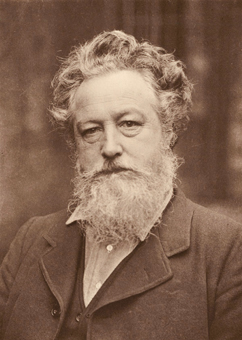

William Morris

William Morris

|

During the nineteenth century, Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle and English social critic John Ruskin warned of the extinction of handicrafts in Europe, due to the Industrial Revolution. This led to English designer and theorist William Morris becoming the father of England's Arts & Crafts Movement. This movement spread to America, where in the early nineteenth century preindustrial craft trades had almost disappeared and early Colonial American and Native American craft roots were giving way to mass produced furniture and items for the home.

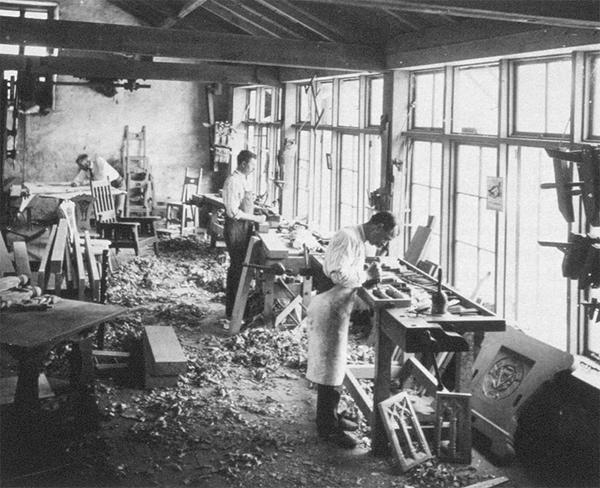

Rose Valley Workshop

Gathering at Byrdcliffe

In the United States, Utopian communities were created around the ideals of the Arts & Crafts Movement as artistic and social experiments. There was Rose Valley, founded by William Lightfoot Price in Pennsylvania in 1901 and the Byrdcliffe Arts and Crafts Colony, founded by Ralph Radcliffe Whitehead and his wife Jane Byrd McCall Whitehead near Woodstock, New York in 1903. This movement toward creating a new way of living close to nature – and seeing Woodstock as a place to create social change – would be mirrored in the later American Studio Craft Movement.

In American cities, projects inspired by the Arts & Crafts Movement were undertaken on a community level, with education in philosophies associated with the movement and the creation of crafts central to the pursuit.

Louis Comfort Tiffany

Louis Comfort Tiffany |

Gustav Stickley

Gustav Stickley |

Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright |

Louis Comfort Tiffany argued for the placement of well-designed and crafted objects in the American home. Gustav Stickley began creating furniture distinguished by simplicity and harmony between interior decorative art and architecture and produced a publication titled "The Craftsman” from 1901 through 1916.

While it originally focused on promoting the ideals of England's Arts and Crafts Movement, "The Craftsman" ultimately developed American craft concepts and had an influence on Frank Lloyd Wright and, ultimately, future generations of American craftsmen, artists and architects.

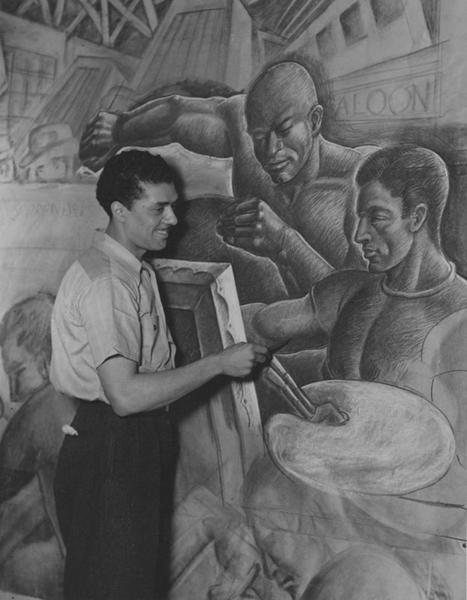

Elmer Brown Painting WPA Mural, late 1930s

Sculptors at work in New York under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration’s

Federal Art Project. The program produced more than 18,800 pieces of sculpture.

(Smithsonian Archives of American Art)

The American Studio Craft Movement began in the wake of World War II – a period of financial prosperity in America. The G.I. bill made it possible to launch careers, designing, creating and marketing work to those who could indulge their tastes and acquire one-of-a-kind objects.

The individuals who created work often did not think of themselves as artists as much as craftspeople. For the most part, they weren’t looking at making a statement with their work or creating something bold and new. They were not looking toward the Arts & Crafts Movement for inspiration as much as being pragmatic in their pursuit of developing a business in which they functioned as designer, creator and marketer.

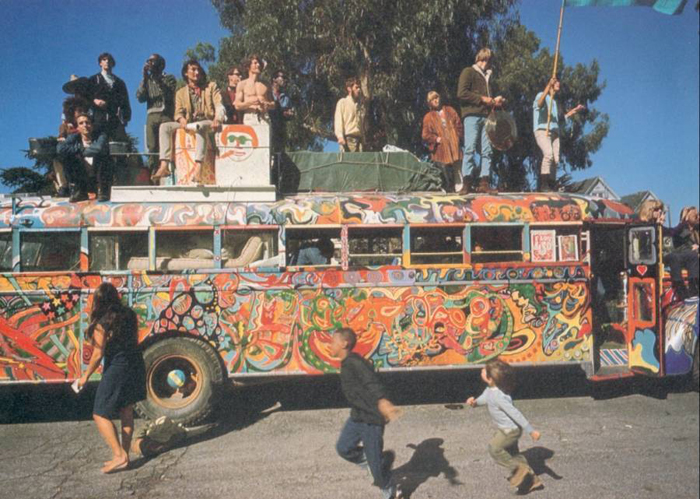

The Merry Pranksters — author Ken Kesey's collective of LSD disciples — atop their bus

Free Concert in Golden Gate Park, 1967

During the years of the Vietnamese conflict, counter-culture and back-to-the-land movements, a new generation of individuals looked to those who had found independence working in craft media and were inspired. Creating works in craft media offered a means of freedom and self-expression that dovetailed nicely with a desire to drop out from conventional society and living rurally, growing and foraging for food, and embracing individuality.

It was again a Utopian idea – that one could create a better world through attention to one’s environment and the objects that were part of daily life.

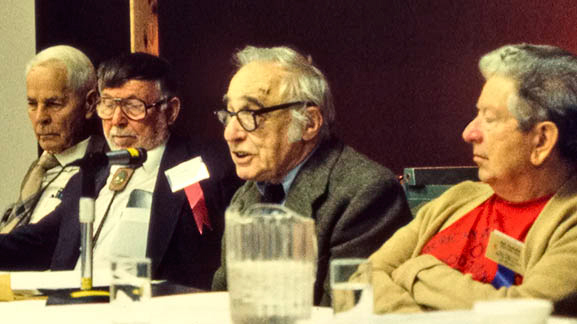

(left to right) Melvin Lindquist, Rude Osolnik, James Prestini and Bob Stocksdale

at the 1988 American Association of Woodturners Symposium. (Photograph by Mark Lindquist)

The aging individuals who had been part of the Post-World War II American Studio Craft Movement were an inspiration, both in their work and with lifestyles that embraced simplicity and freedom to this new generation. There were similar concerns to those who founded the Arts & Crafts Movement, with the soulless mass-produced plastic objects that had become increasingly central to life in the 1960s. It was a quiet revolution in art and design. Rather than joining a firm or going to work for a corporation, the individuals wanted to craft their own lives through designing, creating and marketing unique works using traditional materials and processes. They grew their hair and beards long, interestingly in a manner similar to the founders of the Arts & Crafts Movement.

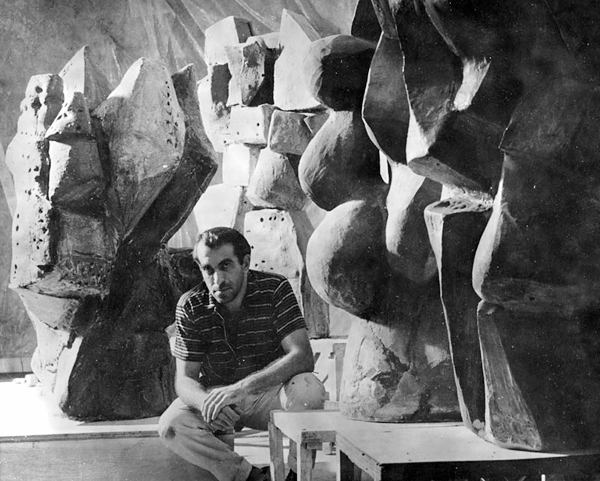

Peter Voulkos in his studio on Glendale Boulevard in Los Angeles, 1959

(Image courtesy of the Voulkos & Co. Catalogue Project)

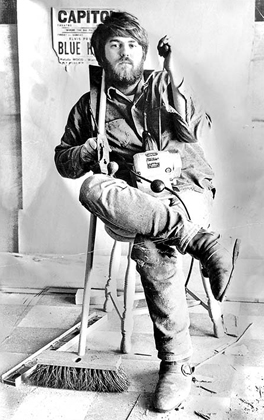

Mark Lindquist, 1969

Mark Lindquist, 1969

Henniker, NH

(Photograph by Darr Collins) |

Wendell Castle, 1969

(Photograph by Doug Stewart. Courtesy Fendrick Gallery Archives)

Wendell Castle, 1969

(Photograph by Doug Stewart. Courtesy Fendrick Gallery Archives) |

During the last two decades of the 20th century, artists working in craft media experimented increasingly with non-traditional approaches, producing bold, abstract, and sculptural art. Utilitarian objects remained an important part of the field, leading many critics to dismiss work in craft media as not worthy of the mantle of art.

What is craft? That’s where it gets a little tricky. According to Merriam-Webster, craft can be a noun or it can be a verb. It can refer to a skill in planning, making, or executing or can refer to an occupation, trade, or activity requiring manual dexterity or artistic skill. As a verb, it can mean to make or produce with care, skill, or ingenuity.

Craft can refer to a process, though for many it refers to media that is traditionally crafted by hand. Craft media traditionally consists of wood, glass, ceramic, fiber and metal, which can manifest as jewelry, furniture, dinnerware, clothing, and wide-ranging functional items. In the last quarter of the 20th century, it came to include non-functional sculpture, narrative and conceptual work.

It could be said that not everything that is crafted is art and that not all art is crafted… although at one point, all artists were craftspeople – for instance, a wood frame had to be crafted and then the canvas stretched and prepared. Paint, prior to mass-manufacture, was carefully created by the artist and the careful application of paint with brushes required craftsmanship, as well as artistic intent.

Painting on canvas didn’t come into common usage until the 16th century during the Italian Renaissance. Conceptualism, which has only been around for a bit over a century. Art, on the other hand, stretches back to when homo sapiens first came into existence and from the beginning utilized media today considered craft media. I’m of course talking about art as a form of creative expression, not the concept of art that some art critics base their opinions on. The history of art as a concept would take us all down a rabbit hole that leads into the realm of theories and philosophy, tangled up in history.

What is important to note is that everything in the art world is always being reassessed. Artists who seemed lost to time are rediscovered, art movements that weren’t considered particularly important at the time are seen in a new light, and historians, museum curators, auction houses and galleries are ever changing the way works are viewed and appreciated.

An excerpt, sharing how Kevin Virgil Wallace, Director of the Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts became involved with the American Studio Craft Movement and how his life was transformed by that involvement.

I was always interested in the arts and knew from a young age that I would make my life in the arts. While in our early twenties, my wife and I were collecting from galleries and at auction, pleasantly surprised that we could acquire signed aquatints and etchings by important Surrealists at prices within our limited budget. I began my study of art history in college, but as an autodidact, I collected and studied art books covering, with a particular interest in, 20th century art.While many people love to study art from different times, I ultimately embraced Ralph Waldo Emerson’s admonition to "accept the place the divine providence has found for you, the society of your contemporaries, the connection of events."

In 1985, my older brother started working at a West Los Angeles gallery that represented artists in the American Studio Craft Movement. It was called del Mano Gallery, which was supposed to mean “of the hand”, in some sort of weird combination of Spanish and Italian. The gallery began in 1973 by a group of artists who felt it was time to graduate from selling work in the park to having a co-op gallery, which they opened in time to take advantage of Christmas sales that year. With time, most of the group dropped out of the enterprise, leaving Jan Peters and Ray Leier to become the gallery owners.

I was something of an art snob at the time and, when we’d go to visit my brother at del Mano Gallery, I voiced my opinion that the work they exhibited wasn’t art. During the holidays in 1986, my older brother convinced my wife Sheryl to come and work there over the holidays. This led to her becoming a full-time employee, with my brother quitting soon after to focus on interior design. I began visiting the gallery often and came to see some of the work – particularly works created in wood – as art created in craft media.

del Mano Gallery

del Mano Gallery |

del Mano Gallery circa 1991

del Mano Gallery circa 1991 |

I was very much interested in the art world and saw that the way del Mano Gallery exhibited work was problematic. While they had a space devoted to larger, more expensive, one-of-a-kind works, they also had a lot of giftable items and jewelry, and the place seemed more like a gift shop for crafts, than a legitimate gallery. I knew that no art critic would ever review any of their exhibitions for this time, which meant no art world credibility. And yet, when I was offered a job as manager at the beginning of 1991, I took it and thus began my involvement with the American Studio Craft Movement.

Prior to this I was dealing in the field of Outsider Art, having developed a friendship with an artist named Reverend Howard Finster. Outsider Art was an unrecognized field at the time and tended to be unsophisticated, poorly constructed and painted, and pretty much the opposite of the standards of craftsmanship that were valued in studio craft. I had been working to get validation for the outsider artists, who tended to be unschooled, and then turned my attention to working to get validation for artists who were part of the American Studio Craft Movement.

I was 32 at the time and was sort of a kid compared to everyone else. The gallery represented some of the artists who had been part of the Post World War II period, who were over 80 years of age at that time. These individuals were considered “elder statesmen” in the field. There were also a number of artists who had been part of the field since the late 60s or early 70s, who tended to be ten to twenty years older than I was. These artists and the collectors very kindly took me under their wing due to my sincere interest and I learned a great deal over those first years. Ultimately, I came to be a leading authority on the field, working with museum curators in selecting works for permanent collections.

I had been hired to manage the gallery but was more interested in exploring other aspects of the art world. I was given the opportunity to train a new manager, who I would oversee, and to create my own title. I chose to be Creative Director, and that was my role until I left the gallery a decade later.

In 1993, I came up with an idea for an exhibition of small works in wood, conceptualizing and curating my first exhibition – Turned Wood: Small Treasures.

The following year, I conceptualized and created an exhibition of teapots by contemporary craft artists, titled Hot Tea, and the year after that, Contemporary Baskets, which shared the wonderful work being created by fiber artists.

The gallery exhibited craft media – glass, ceramic, wood, fiber and metal – but specialized in works in wood, particularly woodturning.

In an effort to reach a larger audience, del Mano Gallery exhibited at the first presentation of SOFA (Sculpture, Objects, Functional Art), an art fair in Chicago. We took contemporary woodturning, which didn’t sell well, and we lost a considerable amount of money. However, we believed that the SOFA art fairs would prove important and continued to attend the one in Chicago, and then for several years one in New York City. Sales improved, prices increased, and the collector base for contemporary art in wood continued to grow.

I felt that, to create validation for the work, there should be a coffee table book on the field – but must admit that one of my ambitions was to become a published author. In 1999 I co-authored a book titled Contemporary Turned Wood: New Perspectives in a Rich Tradition with Ray Leier and Jan Peters. This was followed by two other books that we wrote together for the same company, Baskets: Tradition & Beyond and Contemporary Glass: Color, Light & Form. At the time the third book was published, we learned that the company that published the books was going to discontinue the series.

I had grown restless, as the exhibitions and art fairs became rote and I wanted new experiences. I wanted to write more books and articles and curate museum exhibitions. A number of artists and collectors were hoping that I’d open my own gallery representing wood artists, but del Mano was like an alma mater and I wasn’t interested in competing with them. Instead, I continued to promote their artists by writing and guest-curating museum exhibitions. I worked with a number of art centers and museums, including curating an exhibition about Beatrice Wood for the Folk and Craft Art Museum, Los Angeles. This led to my being invited by the Happy Valley Foundation to create the Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts in 2005, giving a home to the previously created Happy Valley Cultural Center. At the same time, I continued to be involved with writing about and curating exhibitions of artists who were part of the American Studio Craft Movement – particularly those who worked in wood.

Ray Leier and Jan Peters, 2010, at SOFA Chicago

(Photo by Steve Sinner)

Jan Peters passed away the following year, after a twelve-year battle with cancer.

Ray Leier passed away four years after Jan, and del Mano Gallery came to an end.

The closing of the gallery represented the end of an era.

Soon after leaving del Mano Gallery in 2001, I was invited to lunch by Dr. Irving Lipton. I’d known Irv ever since I started working at the gallery, as he had created the largest collection of contemporary wood art internationally. Whenever an artist was in town visiting, he’d throw a dinner party and then everyone would gather at the condominium he’d purchased to house the collection. Like the other artists and collectors, he was supportive of my involvement with the field and would invite me to these events.

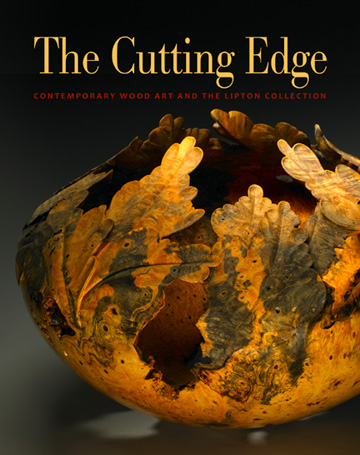

In 2001, Dr. Lipton asked me to assist with his collection, making museums gifts and putting some of the works on the market. He passed away soon after but had made clear to his wife that I should handle the collection, which I continue to care for, on behalf of the family. In 2011, The Lipton family made major gifts of work from the collection to five museums, and I authored the book The Cutting Edge: Contemporary Wood Art & The Lipton Collection in conjunction with these gifts.

The Cutting Edge

Contemporary Wood Art and The Lipton Collection

by Kevin Wallace

We would be happy to send a copy of this book to those who make a donation to support the Center’s programming.

A softcover copy will be sent, postpaid, to anyone who makes a $30 donation.

A hardcover copy will be sent, postpaid, with a $50 donation.

The beautifully designed book shares important works of art in wood and the story of the artists and will be a welcome addition to any library – and a wonderful gift for anyone who works in wood.

Donate $30.00

Receive a softcover edition

|

Donate $50.00

Receive a hardcover edition

|

The Center operates as an activity of the Happy Valley Foundation, a 501 (c)(3),

therefore all donations are fully tax deductible. Tax ID #95-080-9370.

I’m pleased to have the opportunity to share the work of these artists, as well as this history with a larger audience as part of the Center’s educational programming. The exhibition takes its title from the book, which features examples of works given to museums across the country. The majority of the artists in the exhibition are featured in the book and in the permanent collections of a number of museums.

This exhibition, which focuses on the last quarter of the 20th century, is not meant to be encyclopedic or feature every major artist who worked in wood as part of the American Studio Craft Movement. I should also note that wonderful works continue to be created in all craft media, though I've decided to focus my work in the field of wood in documenting and sharing the pioneering artists who were part of the Golden Age of the American Studio Craft Movement. The Center exhibits work in all media, though a significant amount of our exhibitions and workshops focus on works in craft media, as Beatrice Wood was a leading figure in the American Studio Craft Movement. This allows me to continue the work that began over three decades ago.

– Kevin Virgil Wallace

The Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts is Open to the Public

Fri, Sat, & Sun 11:00 am - 5:00 pm.

8585 Ojai-Santa Paula Road, Ojai, CA 93023

805.646.3381

Driving Directions